California of the East

This post is also available in: Lithuanian, Polish, French, German, Italian, Spanish

From a distance, the small two-storey building melts into the grey of Vilnius’ northwestern suburbs. Once past the modest entrance and a small EU flag sticker you only need to go up a few stairs to discover a dozen high-tech laboratories. These belong to the Lithuanian company EKSPLA, owner of some of the most cutting-edge laser factories in Europe. Pure coincidence? Far from it.

Raimonda Sadauskienė, director of the Lithuanian Development Agency, recalls how, ‘during the seventies and eighties, Lithuania was the Silicon Valley of the USSR.’ Over thirty years, this country (the same size as three French counties) saw no less than 3,500 physics Ph.D. students graduate. Her organisation recognises that indeed these are the ‘scientific and technological traditions that have contributed to the success of Lithuania’s transition towards a modern market economy.’

Although consumer electronics have collapsed in recent years, Lithuania is still known for several well-respected disciplines: biotechnology, lasers, mechatronics (a cross between mechanical engineering, electronics and software engineering), and also telecommunications and information technology.

In EKSPLA’s laboratories, every room is equipped with an assembly table, with numerous holes though which dozens of optical elements can be attached, and also a dust extractor for the lasers’ number-one enemy. The technicians and engineers have the task of putting together the various elements that make up the laser, from the power generator to the various amplifiers and optical elements that will allow the desired laser beam to be fixed. The final product may be just a large rectangular grey box, but it can still fetch ‘up to half a million Euros’, according to Laurynas Ukanis, from EKSPLA’s communications department.

Since 2004, when Lithuania joined the European Union, EKSPLA’s turnover has grown by 15% a year. In 2007 her directors banked on sales close to the 10 million Euro mark. EKSPLA counts no less than NASA , IBM, Mitsubishi and some of the world’s most prestigious universities amongst her better-known clients.

Grey matter and precision technology

There are nearly a dozen companies, besides EKSPLA, who are currently producing lasers and optical components for a (still modest) turnover of 15 million Euros. But the 15-20% growth rate is encouraging. The man responsible for this dynamic growth in the laser sector is Algis Piskarskas, the head of the Physics Department at the University of Vilnius.

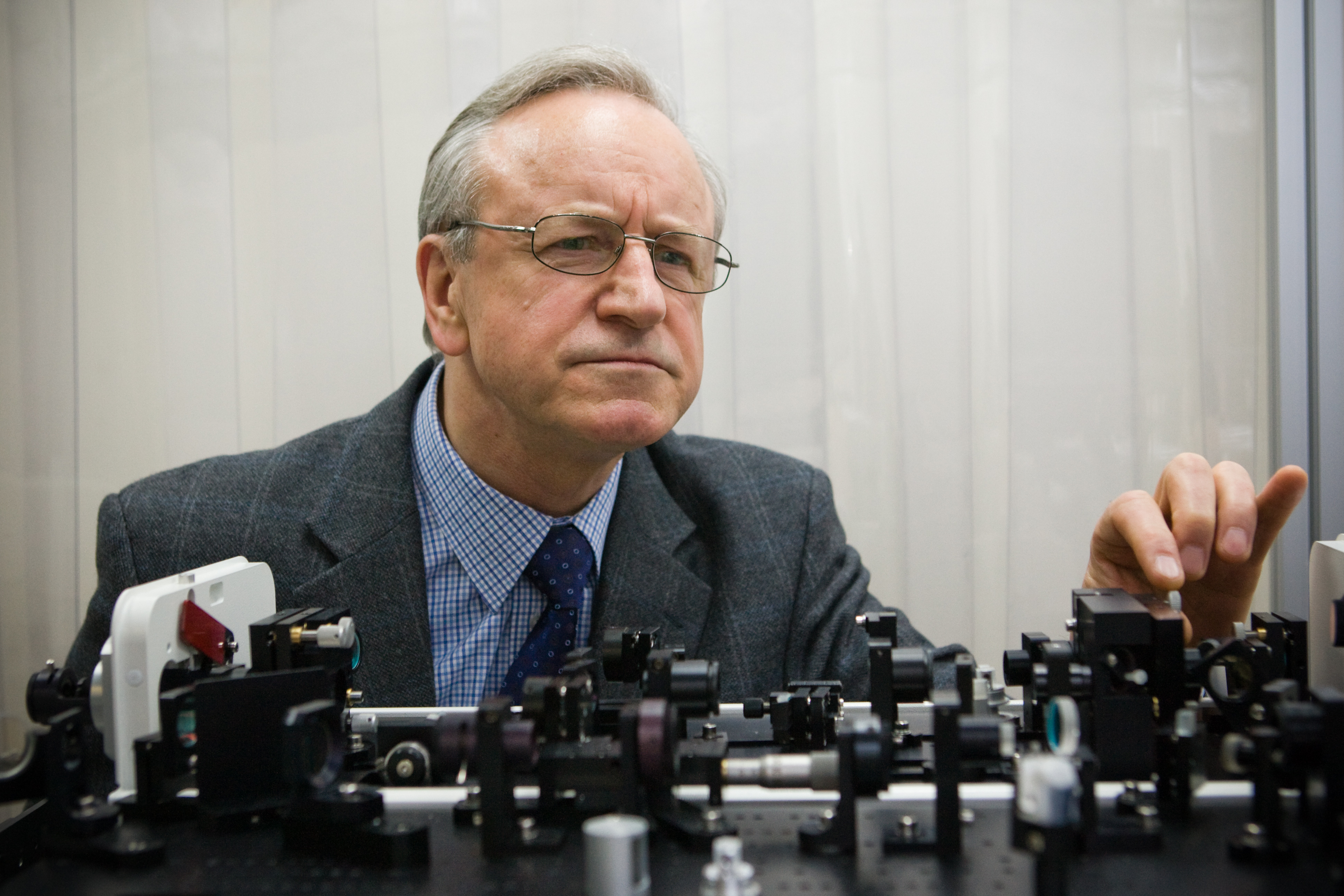

Algis Piskarskas in his laboratory, photo: fotokronika.lt

A true product of Soviet scientific training, this brilliant researcher has revolutionized the laser sector. He meets us in this office on the eighth floor of one of the Saulėtekis campus towers. He has a jovial smile and thin glasses perched on his face. He describes how ‘both the Science Academy and the University of Vilnius have had to find a balance between fundamental and applied research during recent years. This became even more necessary when funds started to run short with the fall of the USSR and Lithuania’s independence in 1990. It was necessary to find industrial applications to survive.’

In this way, not only the two motors of the Lithuanian laser economy: EKSPLA and Standa, but also other new small-to-medium sized companies have sprung up as a result of research. The best example of this is ‘Light Conversion‘, created in 1993 as a result of the development of a unique multicoloured laser in the eighties.

Today this company has an 80% world market share for this laser, and annual sales of close to two million Euros. It has around 30 employees on the University campus, including many Masters students, and works closely with the university of Vilnius in its research and development investments.

Backers: government and the EU

Indeed, as Algis Piskarskas explains, ‘our research has put Lithuania on the map.’ In recent years the Lithuanian government has generally encouraged the development of these industries, particularly by promoting innovation. It was behind a national agreement to try and go from 2003’s growth level (7% of GDP) to 25% in 2015.

The Lithuanian president, Valdas Adamkus, has also been talking this up abroad. In his first official visit to America’s west coast in February 2007 he spoke of how Lithuania has a ‘pool of intellectual potential which gives us high hopes for development of the high-tech sector.’

More than anything else though, Lithuania has been able to dream bigger since joining the European Union. The European Commission has named the Center for Laser Research at the University of Vilnius a European Centre of Excellence, which has brought considerable investment and renovation. The Centre’s director underlines, with satisfaction, how “we received funding to the tune of 3.5 million Euros, to run three large projects with various businesses such as EKSPLA and Light Conversion as part of European R&D projects.

European California

Another project involving Algis Piskarskas and his acolytes is the local ‘Sunrise Valley‘ scheduled for 2008. The first two buildings of this ‘Made in Lithuania’ business complex should grow up just a few dozen metres away from the University laboratories by 2008. The project manager, Andrius Bagdonas, explains that the goal is ‘to bring together on one site, the city’s two universities, both general and technical, high-tech businesses and support services such as a technology transfer centre and a business angels network.’

Another project involving Algis Piskarskas and his acolytes is the local ‘Sunrise Valley‘ scheduled for 2008. The first two buildings of this ‘Made in Lithuania’ business complex should grow up just a few dozen metres away from the University laboratories by 2008. The project manager, Andrius Bagdonas, explains that the goal is ‘to bring together on one site, the city’s two universities, both general and technical, high-tech businesses and support services such as a technology transfer centre and a business angels network.’

Between now and 2015, and the support of the two other ‘valleys’ (biotechnology in Vilnius and mechatronics in Kaunas (the country’s second city), Lithuania wants to become, once again, the Baltic Silicon Valley, connecting 500 small and medium sized businesses in state-of-the-art technology. This is an ambitious goal. But Lithuania can now count upon 600 million Euros of structural funds from the European Union, donated for research and development investment until 2013.

AUTHOR Philippe Jacqué, TRANSLATOR Veronica Newington

English

English Lithuanian

Lithuanian Polish

Polish French

French German

German Italian

Italian Spanish

Spanish